Out of all the experiences I have had over the 23 years I have lived in Israel, a recent excursion to a Steimatzky bookseller on Jerusalem’s Emek Refaim Street may have been the most ironic of all. I had entered the store looking for Eilu v’Eilu, a collection of short stories by S.Y. Agnon, Israel’s most celebrated author and only Nobel laureate for literature. But the salesman’s reply when I asked for the book left me speechless: They only keep Agnon in stock today in English translation.

To be fair, the translation they did have in stock — 15 volumes of Agnon’s writings, published by Toby Press and edited by Rabbi Jeffrey Saks — is extraordinary.

The series, which was completed last month, does not follow any particular sub-set of Agnon’s work but rather draws on a variety of the author’s corpus — from semi-autobiographical tales about his childhood, recounted in A City and Its Fullness, to the wholly fictional Two Scholars That Were in Our Town and Other Novellas, and again to short stories such as Yisakhar and Zevulun and The Tale of Rabbi Gadiel, heavily influenced by traditional rabbinic homilies (midrashim) — is a comprehensive work that both captures the music and flavor of Agnon’s Hebrew prose and also provides a rich collection of forewords and afterwords written by Agnon scholars.

Each volume of the series also contains a wealth of annotations to explain historical context, liturgical references and detailed explanations in instances where translators and editors found the original texts to be impossible to render into English.

The accomplishment is not an obvious one, for at first thought, reading Agnon in translation makes little sense, much like the idea of reading a Hebrew-language version of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Twain’s written version of the spoken dialect of that time and place is so central to his portrayal of 19th-century Missouri that it renders the text nearly impossible to translate out of English.

So, too, for Agnon, in the other direction.

Born in 1887 as Shmuel Yosef Halevi Czaczkes in the Galician town of Buczacz (he claimed to have been born in 1888, possibly to avoid the Austro-Hungarian army draft), Agnon arrived in Palestine at the age of 20, having been raised in a traditional and Zionist home but without much formal education.

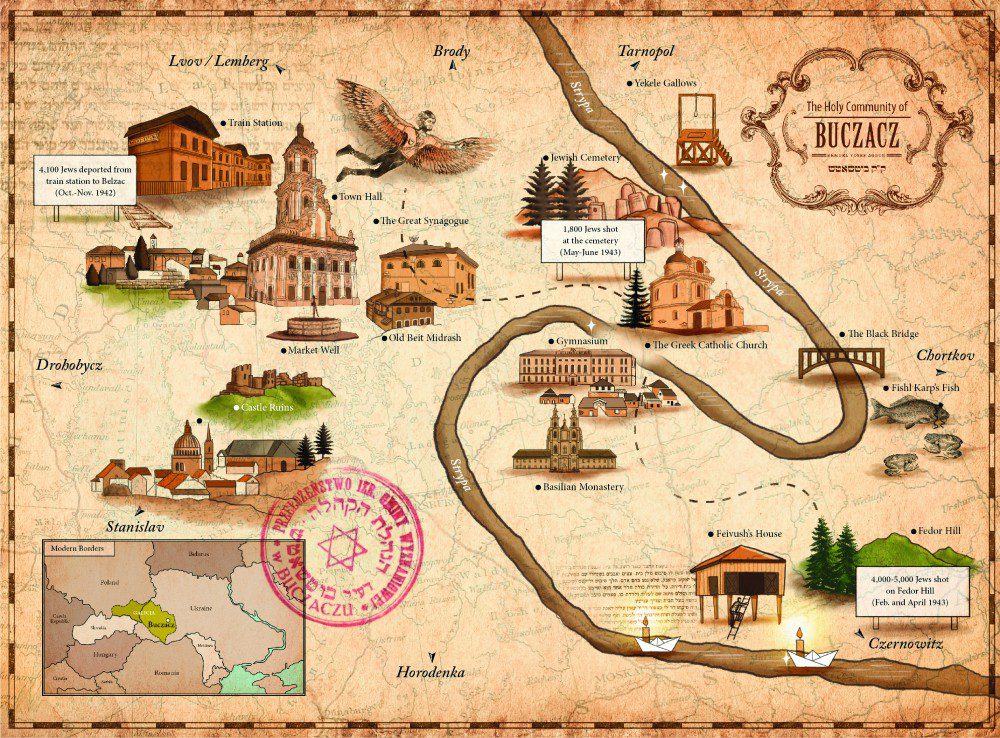

A map of SY Agnon’s Buczacz

As a child and teenager he had studied Torah with his father, but in many ways Agnon’s upbringing was also strikingly open for the time, especially for an Orthodox family. In addition to Torah study, the teenage Czaczkes took advantage of the community’s rich library of secular literature, another example of the Agnon’s comparatively “liberal” upbringing.

That exposure to both traditional and secular literature created a written style and language that is both steeped in Jewish history and tradition, and also draws deeply on the prevailing Zionist winds blowing at the time.

Ironically, however, that combination may make Israel’s most famous author more accessible to some English speakers than to many modern-day Israelis.

“Take an individual who cannot or will not read a novel in Hebrew. But this person may well be able to sit down to study the Talmud or rabbinic commentaries on the Torah,” said Rabbi Jeffrey Saks. “But in some ways those people are better equipped to read Agnon in a good translation than their Israeli neighbors are to read him in the original Hebrew.

“Let me illustrate with a story: I was teaching a course in English at Beit Agnon in Jerusalem about a year ago, when a young Israeli woman with excellent English asked if she could come to the lectures. Of course I said ‘yes,’ but when we read a story about a melaveh malka — that is a traditional post-Sabbath meal that is meant to ‘escort the Sabbath queen’ as she leaves the home and the family begins a new week — she had never even heard the phrase melaveh malka. But the traditional and Orthodox participants all knew what a melaveh malka was.

“So ironically, you see that Agnon is sometimes more accessible in translation to individuals with a background in Jewish learning and tradition than he is in the original Hebrew to Israelis who are often three or four generations removed from any connection to these concepts,” Saks said.

Agnon’s relevance to modern Jews can be seen in English-speaking Jewish communities and academic programs that focus on modern Hebrew literature.

In addition to Saks’ English-language courses on Agnon in Jerusalem (which are broadcast internationally through WebYeshiva), Agnon reading groups have sprouted up in recent years around the world, from Toronto, Canada to Melbourne, Australia to New York City and farther afield.

Gershon Scholem, Agnon’s contemporary who gained fame for his scholarly research on kabbalah, the Jewish mystical tradition, said Agnon existed “at a crossroads” of the old and new worlds, between traditional Judaism and the ideal of the “new Jew” promoted by secular Zionism.

Saks is critical of Israeli schools for what he says is a systemic “phobia” about Agnon. He notes that the linguistic distance between modern-day Israelis and Agnon is far smaller than the average English reader and Shakespeare. He compares the issue to studying the Bible, which is compulsory in government schools, even given the outdated language.

But the reticence of many Israelis — or perhaps of Israeli society as a whole — may stem from exactly the crossroads described by Scholem. That is, Israelis may be “afraid” to study Agnon not because of a language barrier, but precisely because Agnon represents a challenge to the prevailing ethic of socialist Zionism: Crafting a New Jew, breaking off the shackles of religious observance, creating a messianic new world more in line with John Lennon’s Imagine utopia than with a descendant of King David riding into Jerusalem on a white horse.

For a society still defined in many ways by that ethos, Agnon’s modern presentation of modern society as viewed through a lens of traditional religious practice and Jewish sources — or perhaps his presentation of Jewish tradition and sources through a lens of the modern world — presents not a linguistic challenge, but rather a cultural one.